The last month, it seems like in my ecosystem, people are incredibly focused on “THE BOM” combined with AI agents working around the clock. One of the reasons I have this impression, of course, is my irregular participation in the Future of PLM panel discussions, moderated and organized by Michael Finocharrio.

Yesterday, the continuously growing Future of PLM team held another interesting discussion: “A BOMversation”. You can watch the replay and the comments during the debate here: To BOM or Not to BOM: A BOMversation

On the other hand, there is Prof. Jorg Fischer with his provocative post: 📌 2026 – The year we have to unlearn BOMs! –

On the other hand, there is Prof. Jorg Fischer with his provocative post: 📌 2026 – The year we have to unlearn BOMs! –

Sounds like a dramatic opening, but when you read his post and my post below, you will learn that there is a lot of (conceptual) alignment.

Then there are PLM vendors who announce “next-generation BOM management,” startup companies that promise AI-powered configuration engines, and consultants who explain how the BOM has become the foundation of digital transformation. (I do not think so)

And as Anup Karumanchi states, BOMs can be the reason if production keeps breaking.

I must confess that I also have a strong opinion about the various BOMs and their application in multiple industries.

I must confess that I also have a strong opinion about the various BOMs and their application in multiple industries.

My 2019 blog post: The importance of EBOM and MBOM is in the top 3 of most-read posts. BOM discussions, single BOM, multiview BOM, etc., always attract an audience.

I continuously observe a big challenge at the companies I am working with – the difference between theory and reality.

![]() If the BOM is so important, why do so many organizations still struggle to make it work across engineering, manufacturing, supply chain, and service?

If the BOM is so important, why do so many organizations still struggle to make it work across engineering, manufacturing, supply chain, and service?

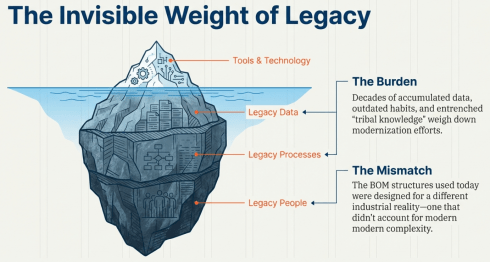

The answer is two-fold: LEGACY DATA, PROCESSES and PEOPLE, and the understanding that the BOM we are using today was designed for a different industrial reality.

Let me share my experiences, which take longer to digest than an entertaining webinar.

Some BOM history and theory

Historically, the BOM was a production artifact. It described what was needed to build something and in what quantities. When PLM systems emerged, the 3D CAD model structure became the authoritative structure representing product definition, driven mainly by the PLM vendors with dominant 3D CAD tools in their portfolio.

Historically, the BOM was a production artifact. It described what was needed to build something and in what quantities. When PLM systems emerged, the 3D CAD model structure became the authoritative structure representing product definition, driven mainly by the PLM vendors with dominant 3D CAD tools in their portfolio.

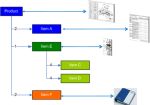

As the various disciplines in the company were not integrated at all, the BOM structure derived from the 3D CAD model was often a simplified way to prepare a BOM for ERP. The transfer to ERP was done manually (retype the structure in ERP), advanced (using Excel export and import with some manipulation) or advanced through an “intelligent” interface.

![]() There are still a lot of companies working this way, probably because, due to the siloed organization, there is no one owning or driving a smooth flow of information in the company.

There are still a lot of companies working this way, probably because, due to the siloed organization, there is no one owning or driving a smooth flow of information in the company.

The need for an eBOM and mBOM

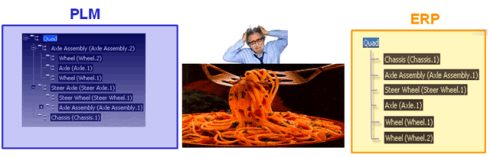

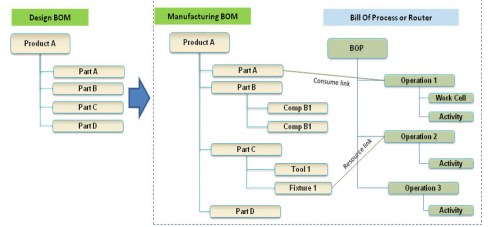

When companies become more mature and start to implement a PLM system, they will discover, depending on their core business processes, that it makes sense to split the BOM concept into a specification structure, the eBOM and a manufacturing structure for ERP, the mBOM.

The advantage of this split is that the engineering specification can remain stable over time, as it provides a functional view of the product with its functional assemblies and part definitions.

This definition needs to be resolved and adapted for a specific plant with its local suppliers and resources. PLM systems often support the transformation from the eBOM to a proposed mBOM, and if done more completely with a Bill of Process.

This definition needs to be resolved and adapted for a specific plant with its local suppliers and resources. PLM systems often support the transformation from the eBOM to a proposed mBOM, and if done more completely with a Bill of Process.

The advantages of a split in an eBOM and an mBOM are:

- Reduced the number of engineering changes when supplier parts change

- Centralized control of all product IP related to its specifications (eBOM/3DCAD)

- Efficient support for modularity, as each module has its own lifecycle and can be used in multiple products.

Implementing an eBOM/mBOM concept

The theory, the methodology and implementation are clear, and you can ask ChatGPT and others to support you in this step.

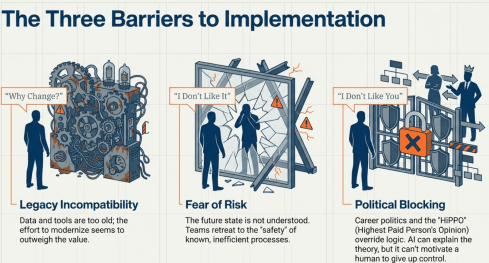

However where ChatGPT or service providers often fail is to motivate a company to move to this next steps, as either their legacy data and tools are incompatible (WHY CHANGE?), the future is not understood and feels risky (I DON’T LIKE IT) or for political career reasons a change is blocked (I DON’T LIKE YOU or the HIPPO says differently)

Extending to the sBOM

When you sell products in large volumes, like cars or consumer products, companies have discovered and organized a well-established service business, as the margins are high here.

Companies that sell almost unique solutions for customers, batch-size 1 or small series, are also discovering or asked by their customers to come up with service plans and related pricing.

The challenge for these companies is that there is a lot of guesswork to be done, as the service business was not planned in their legacy business. A quick and dirty solution was to use the mBOM in ERP as the source of information. However, the ERP system usually does not provide any context information, such as where the part is located and what potential other parts need to be replaced—a challenging job for service engineers.

The challenge for these companies is that there is a lot of guesswork to be done, as the service business was not planned in their legacy business. A quick and dirty solution was to use the mBOM in ERP as the source of information. However, the ERP system usually does not provide any context information, such as where the part is located and what potential other parts need to be replaced—a challenging job for service engineers.

A less quick and still a little dirty solution was create a new structure in the PLM system, which provided the service kits and service parts for the defined product, preferably done based on the eBOM, if an eBOM exists.

![]() The ideal solution would be that service engineers are working in parallel and in the same environment as the other engineers, but this requires an organisational change.

The ideal solution would be that service engineers are working in parallel and in the same environment as the other engineers, but this requires an organisational change.

The organization often becomes the blocker.

As long as the PLM system is considered a tool for engineering, advanced extensions to other disciplines will be hard to achieve.

A linear organization aligned with a traditional release process will have difficulties changing to work with a common PLM backbone that satisfies engineering, manufacturing engineering and service engineering at the same time.

Now, the term PLM becomes Product Lifecycle MANAGEMENT and this brings us to the core issue: the BOM is too often reduced to a parts list without understanding the broader context of the product, needed for service or operation support where artifacts can be hardware and software in a system.

What is really needed is an extended data model with at least a logical product structure that can represent multiple views of the same product: engineering intent, manufacturing reality, service configuration, software composition, and operational context. These views should not be separate silos connected by fragile integrations. They should be derived from a shared, consistent digital infrastructure – this is what I extract from Prof. Jorg Fischer’s post, be it that he comes with a strong SAP background and focus on CTO+

Most companies are still organized around linear processes with a focus on mechanical products: engineering hands over to manufacturing, manufacturing hands over to service, and feedback loops are weak or nonexistent.

Most companies are still organized around linear processes with a focus on mechanical products: engineering hands over to manufacturing, manufacturing hands over to service, and feedback loops are weak or nonexistent.

Changing the BOM without changing the organization is like repainting a house with structural cracks. It may look better, but the underlying issues remain.

Listen to this snippet from the BOMversation where Patrick Hilberg touches this point too.

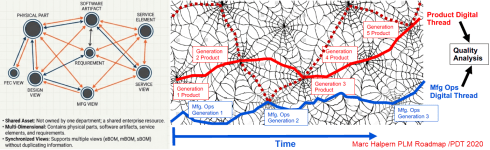

With this approach, the digital thread becomes more than a buzzword. A digital thread must provide digital continuity, which means that changes propagate across domains, that data is contextualized, and that lifecycle feedback flows back into product development. Without this continuity, digital twins concepts remain isolated models rather than living representations of real products.

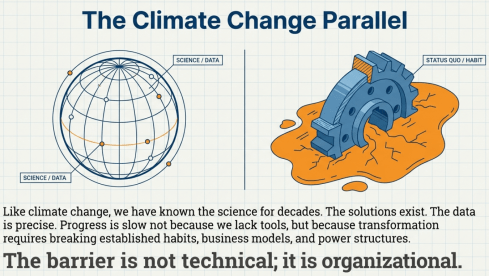

![]() However, the most significant barrier is not technical. It is organizational. There is an interesting parallel with how we address climate change and are willing to take action against it.

However, the most significant barrier is not technical. It is organizational. There is an interesting parallel with how we address climate change and are willing to take action against it.

For decades, we have known what needs to change. The science is precise. The solutions exist. Yet progress is slow because transformation requires breaking established habits, business models, and power structures.

Digital transformation in product lifecycle management follows a similar pattern. Everyone agrees that data silos are a problem. Everyone wants “end-to-end visibility.” Yet few organizations are willing to rethink ownership of product data and processes fundamentally.

So what does the future BOM look like?

It is not a single hierarchical tree. It is part of a maze; some will say it is a graph. It is a connected network of product-related information: physical components, software artifacts, service elements, configurations, requirements, and operational data. It supports multiple synchronized views without duplicating information. It evolves as products change when operated in the field.

Most importantly, it is not owned by one department. It becomes a shared enterprise asset – with shared accountability for various datasets. But we should not abandon the BOM concept. On the contrary, the BOM remains essential and managing BOMs consistently is already a challenge.

But its role must shift from being a collection of static structures to becoming part of the digital product definition infrastructure, extended by a logical product structure and beyond – the MBSE question.

![]() The BOM is not dead. But the traditional BOM mindset is no longer sufficient. The question is not whether the BOM will change. It already is. The real question is whether organizations are ready to change with it.

The BOM is not dead. But the traditional BOM mindset is no longer sufficient. The question is not whether the BOM will change. It already is. The real question is whether organizations are ready to change with it.

Conclusion

Inspired by various BOMversations and AI graphical support, I tried to reflect the business reality, observed for over 10++ years. Technology and the Academic truth do not create breakthroughs in organisations due to the big legacy and fear of failure. Will AI fix this gap, as many software vendors believe, or do we need a new generation with no legacy PLM experience, as some others suggest? Your thoughts?

p.s. My trick to join the BOMversation without being thrown from the balcony 🙃

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article