You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Data Governance’ tag.

The title of this post is chosen influenced by one of Jan Bosch’s daily reflections # 156: Hype-as-a-Service. You can read his full reflection here.

His post reminded me of a topic that I frequently mention when discussing modern PLM concepts with companies and peers in my network. Data Quality and Data Governance, sometimes, in the context of the connected digital thread, and more recently, about the application of AI in the PLM domain.

I’ve noticed that when I emphasize the importance of data quality and data governance, there is always a lot of agreement from the audience. However, when discussing these topics with companies, the details become vague.

Yes, there is a desire to improve data quality, and yes, we push our people to improve the quality processes of the information they produce. Still, I was curious if there is an overall strategy for companies.

And who to best talk to? Rob Ferrone, well known as “The original Product Data PLuMber” – together, we will discuss the topic of data quality and governance in two posts. Here is part one – defining the playground.

The need for Product Data People

During the Share PLM Summit, I was inspired by Rob’s theatre play, “The Engineering Murder Mystery.” Thanks to the presence of Michael Finocchiaro, you might have seen the play already on LinkedIn – if you have 20 minutes, watch it now.

Rob’s ultimate plea was to add product data people to your company to make the data reliable and flow. So, for me, he is the person to understand what we mean by data quality and data governance in reality – or is it still hype?

What is data?

Hi Rob, thank you for having this conversation. Before discussing quality and governance, could you share with us what you consider ‘data’ within our PLM scope? Is it all the data we can imagine?

Hi Rob, thank you for having this conversation. Before discussing quality and governance, could you share with us what you consider ‘data’ within our PLM scope? Is it all the data we can imagine?

I propose that relevant PLM data encompasses all product-related information across the lifecycle, from conception to retirement. Core data includes part or item details, usage, function, revision/version, effectivity, suppliers, attributes (e.g., cost, weight, material), specifications, lifecycle state, configuration, and serial number.

I propose that relevant PLM data encompasses all product-related information across the lifecycle, from conception to retirement. Core data includes part or item details, usage, function, revision/version, effectivity, suppliers, attributes (e.g., cost, weight, material), specifications, lifecycle state, configuration, and serial number.

Secondary data supports lifecycle stages and includes requirements, structure, simulation results, release dates, orders, delivery tracking, validation reports, documentation, change history, inventory, and repair data.

Tertiary data, such as customer information, can provide valuable support for marketing or design insights. HR data is generally outside the scope, although it may be referenced when evaluating the impact of PLM on engineering resources.

What is data quality?

Now that we have a data scope in mind, I can imagine that there is also some nuance in the term’ data quality’. Do we strive for 100% correct data, and is the term “100 % correct” perhaps too ambitious? How would you define and address data quality?

Now that we have a data scope in mind, I can imagine that there is also some nuance in the term’ data quality’. Do we strive for 100% correct data, and is the term “100 % correct” perhaps too ambitious? How would you define and address data quality?

You shouldn’t just want data quality for data quality’s sake. You should want it because your business processes depend on it. As for 100%, not all data needs to be accurate and available simultaneously. It’s about having the proper maturity of data at the right time.

You shouldn’t just want data quality for data quality’s sake. You should want it because your business processes depend on it. As for 100%, not all data needs to be accurate and available simultaneously. It’s about having the proper maturity of data at the right time.

For example, when you begin designing a component, you may not need to have a nominated supplier, and estimated costs may be sufficient. However, missing supplier nomination or estimated costs would count against data quality when it is time to order parts.

And these deliverable timings will vary across components, so 100% quality might only be achieved when the last standard part has been identified and ordered.

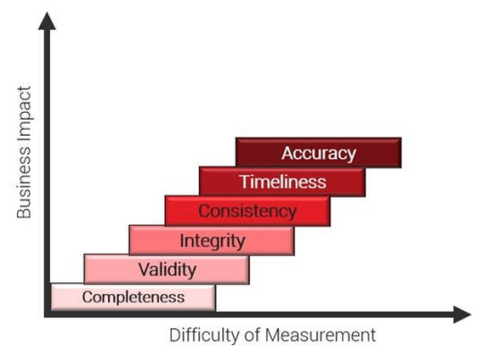

It is more important to know when you have reached the required data quality objective for the top-priority content. The image below explains the data quality dimensions:

- Completeness (Are all required fields filled in?)

KPI Example: % of product records that include all mandatory fields (e.g., part number, description, lifecycle status, unit of measure)

- Validity (Do values conform to expected formats, rules, or domains?)

KPI Example: % of customer addresses that conform to ISO 3166 country codes and contain no invalid characters

- Integrity (Do relationships between data records hold?)

KPI Example: % of BOM records where all child parts exist in the Parts Master and are not marked obsolete

- Consistency (Is data consistent across systems or domains?)

KPI Example: % of product IDs with matching descriptions and units across PLM and ERP systems

- Timeliness (Is data available and updated when needed?)

KPI Example: % of change records updated within 24 hours of approval or effective date

- Accuracy (Does the data reflect real-world truth?)

KPI Example: % of asset location records that match actual GPS coordinates from service technician visits

Define data quality KPIs based on business process needs, ensuring they drive meaningful actions aligned with project goals.

While defining quality is one challenge, detecting issues is another. Data quality problems vary in severity and detection difficulty, and their importance can shift depending on the development stage. It’s vital not to prioritize one measure over others, e.g., having timely data doesn’t guarantee that it has been validated.

While defining quality is one challenge, detecting issues is another. Data quality problems vary in severity and detection difficulty, and their importance can shift depending on the development stage. It’s vital not to prioritize one measure over others, e.g., having timely data doesn’t guarantee that it has been validated.

Like the VUCA framework, effective data quality management begins by understanding the nature of the issue: is it volatile, uncertain, complex, or ambiguous?

Not all “bad” data is flawed, some may be valid estimates, changes, or system-driven anomalies. Each scenario requires a tailored response; treating all issues the same can lead to wasted effort or overlooked insights.

Furthermore, data quality goes beyond the data itself—it also depends on clear definitions, ownership, monitoring, maintenance, and governance. A holistic approach ensures more accurate insights and better decision-making throughout the product lifecycle.

KPIs?

In many (smaller) companies KPI do not exist; they adjust their business based on experience and financial results. Are companies ready for these KPIs, or do they need to establish a data governance baseline first?

In many (smaller) companies KPI do not exist; they adjust their business based on experience and financial results. Are companies ready for these KPIs, or do they need to establish a data governance baseline first?

Many companies already use data to run parts of their business, often with little or no data governance. They may track program progress, but rarely systematically monitor data quality. Attention tends to focus on specific data types during certain project phases, often employing audits or spot checks without establishing baselines or implementing continuous monitoring.

Many companies already use data to run parts of their business, often with little or no data governance. They may track program progress, but rarely systematically monitor data quality. Attention tends to focus on specific data types during certain project phases, often employing audits or spot checks without establishing baselines or implementing continuous monitoring.

This reactive approach means issues are only addressed once they cause visible problems.

When data problems emerge, trust in the system declines. Teams revert to offline analysis, build parallel reports, and generate conflicting data versions. A lack of trust worsens data quality and wastes time resolving discrepancies, making it difficult to restore confidence. Leaders begin to question whether the data can be trusted at all.

Data governance typically evolves; it’s challenging to implement from the start. Organizations must understand their operations before they can govern data effectively.

Data governance typically evolves; it’s challenging to implement from the start. Organizations must understand their operations before they can govern data effectively.

In start-ups, governance is challenging. While they benefit from a clean slate, their fast-paced, prototype-driven environment prioritizes innovation over stable governance. Unlike established OEMs with mature processes, start-ups focus on agility and innovation, making it challenging to implement structured governance in the early stages.

Data governance is a business strategy, similar to Product Lifecycle Management.

Before they go on the journey of creating data management capabilities, companies must first understand:

- The cost of not doing it.

- The value of doing it.

- The cost of doing it.

What is the cost associated with not doing data quality and governance?

Similar to configuration management, companies might find it a bureaucratic overhead that is hard to justify. As long as things are going well (enough) and the company’s revenue or reputation is not at risk, why add this extra work?

Similar to configuration management, companies might find it a bureaucratic overhead that is hard to justify. As long as things are going well (enough) and the company’s revenue or reputation is not at risk, why add this extra work?

Product data quality is either a tax or a dividend. In Part 2, I will discuss the benefits. In Part 1, this discussion, I will focus on the cost of not doing it.

Product data quality is either a tax or a dividend. In Part 2, I will discuss the benefits. In Part 1, this discussion, I will focus on the cost of not doing it.

Every business has stories of costly failures caused by incorrect part orders, uncommunicated changes, or outdated service catalogs. It’s a systematic disease in modern, complex organisations. It’s part of our day-to-day working lives: multiple files with slightly different file names, important data hidden in lengthy email chains, and various sources for the same information (where the value differs across sources), among other challenges.

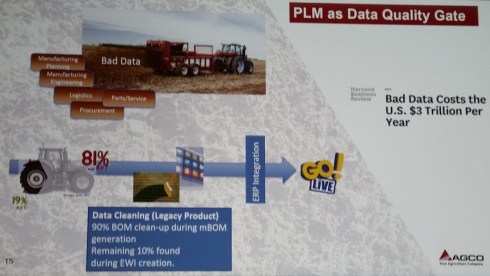

Above image from Susan Lauda’s presentation at the PLMx 2018 conference in Hamburg, where she shared the hidden costs of poor data. Please read about it in my blog post: The weekend after PLMx Hamburg.

Above image from Susan Lauda’s presentation at the PLMx 2018 conference in Hamburg, where she shared the hidden costs of poor data. Please read about it in my blog post: The weekend after PLMx Hamburg.

Poor product data can impact more than most teams realize. It wastes time—people chase missing info, duplicate work, and rerun reports. It delays builds, decisions, and delivery, hurting timelines and eroding trust. Quality drops due to incorrect specifications, resulting in rework and field issues. Financial costs manifest as scrap, excess inventory, freight, warranty claims, and lost revenue.

Poor product data can impact more than most teams realize. It wastes time—people chase missing info, duplicate work, and rerun reports. It delays builds, decisions, and delivery, hurting timelines and eroding trust. Quality drops due to incorrect specifications, resulting in rework and field issues. Financial costs manifest as scrap, excess inventory, freight, warranty claims, and lost revenue.

Worse, poor data leads to poor decisions, wrong platforms, bad supplier calls, and unrealistic timelines. It also creates compliance risks and traceability gaps that can trigger legal trouble. When supply chain visibility is lost, the consequences aren’t just internal, they become public.

For example, in Tony’s Chocolonely’s case, despite their ethical positioning, they were removed from the Slave Free Chocolate list after 1,700 child labour cases were discovered in their supplier network.

The good news is that most of the unwanted costs are preventable. There are often very early indicators that something was going to be a problem. They are just not being looked at.

Better data governance equals better decision-making power.

Visibility prevents the inevitable.

Conclusion of part 1

Thanks to Rob’s answers, I am confident that you now have a better understanding of what Data Quality and Data Governance mean in the context of your business. In addition, we discussed the cost of doing nothing. In Part 2, we will explore how to implement it in your company, and Rob will share some examples of the benefits.

Feel free to post your questions for the original Product Data PLuMber in the comments.

Four years ago, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we discussed the critical role of a data plumber.

Interesting reflection, Jos. In my experience, the situation you describe is very recognizable. At the company where I work, sustainability…

[…] (The following post from PLM Green Global Alliance cofounder Jos Voskuil first appeared in his European PLM-focused blog HERE.) […]

[…] recent discussions in the PLM ecosystem, including PSC Transition Technologies (EcoPLM), CIMPA PLM services (LCA), and the Design for…

Jos, all interesting and relevant. There are additional elements to be mentioned and Ontologies seem to be one of the…

Jos, as usual, you've provided a buffet of "food for thought". Where do you see AI being trained by a…